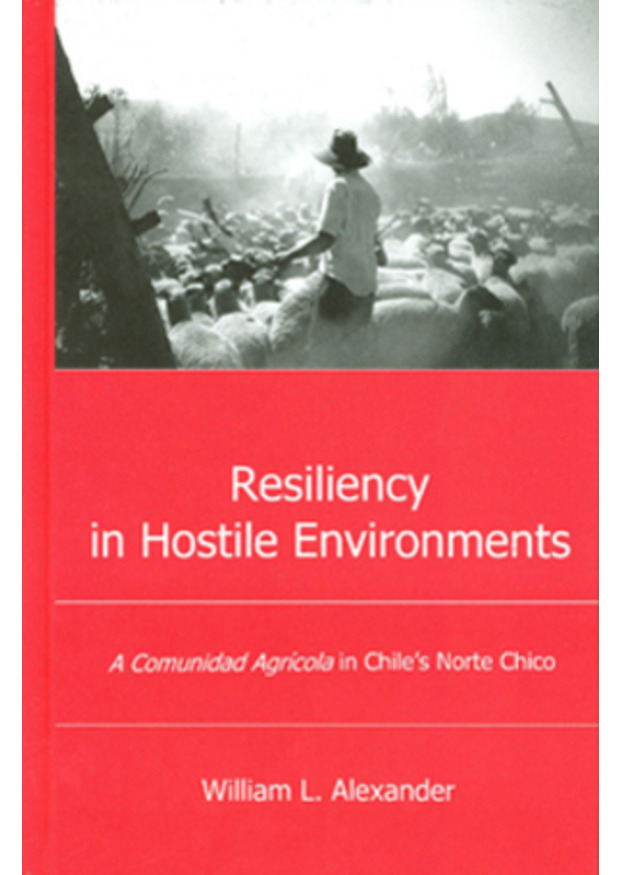

A Comunidad Agrícola in Chile's Norte Chico

This book is the first published ethnography of "comunero culture" in an agricultural community in the Coquimbo region of Chile. In this unforgiving environment of limited resources and cyclical drought, the comunidades agrícolas have developed unique systems comprised of indivisible communal land, inherited land-use rights, local-level consensus building, cooperative relations of production and resource conservation, and diverse economic activities closely linked to changing environmental conditions. Based on fieldwork spanning several years, the book brings to light a determined struggle to protect land and livelihood through vivid details of daily life in a peasant community, forms of mutual assistance, and relations with state and developmental agencies. One particular family's story is told to illustrate the extraordinary resiliency of these communities in response to the sometimes harsh natural, sociopolitical, and economic development environments in which they are situated. Focusing on the strength of cultural expression as well as environmental adaptation, this work challenges many conventional notions about seemingly marginalized people living in marginal lands.

For ethnographers this study offers a rich account of cultural life across years of plenty and years of scarcity, including itinerant seasons of pastoral migration during periods of drought. Dr. Alexander's analysis of large scale economic development—particularly copper mining in the region―on both the natural environment and on comunero culture and consciousness will interest ecological anthropologists and environmental historians, especially those in the critical subfield of political ecology. Applied anthropologists and development specialists will find relevant examples in his critique of policies and programs informed by the neoliberal discourse of modernization and standardization that limit the traditionally flexible livelihood options of community members.

Resiliency in Hostile Environments places these issues within the political economy of Chile's "transition to democracy," an era of significant interest to students and scholars of post dictatorship Latin American societies. While comunero democracy has been revitalized since the return of civilian rule, the failure of some rural assistance programs is often attributed to the government's continued use of the dictatorship's model of economic development that sometimes conflicts with local ideals and practices. The book re-energizes peasant studies and articulation of modes of production theory in its argument for the persistence of these agricultural communities. This book gives voice to these inspirational people and reflects upon the author's personal relationships and experiences in Chile's "Little North."