*this transcript has been edited from the original audio for readability and length. Listen to the entire episode on Spotify and Apple.

NRC

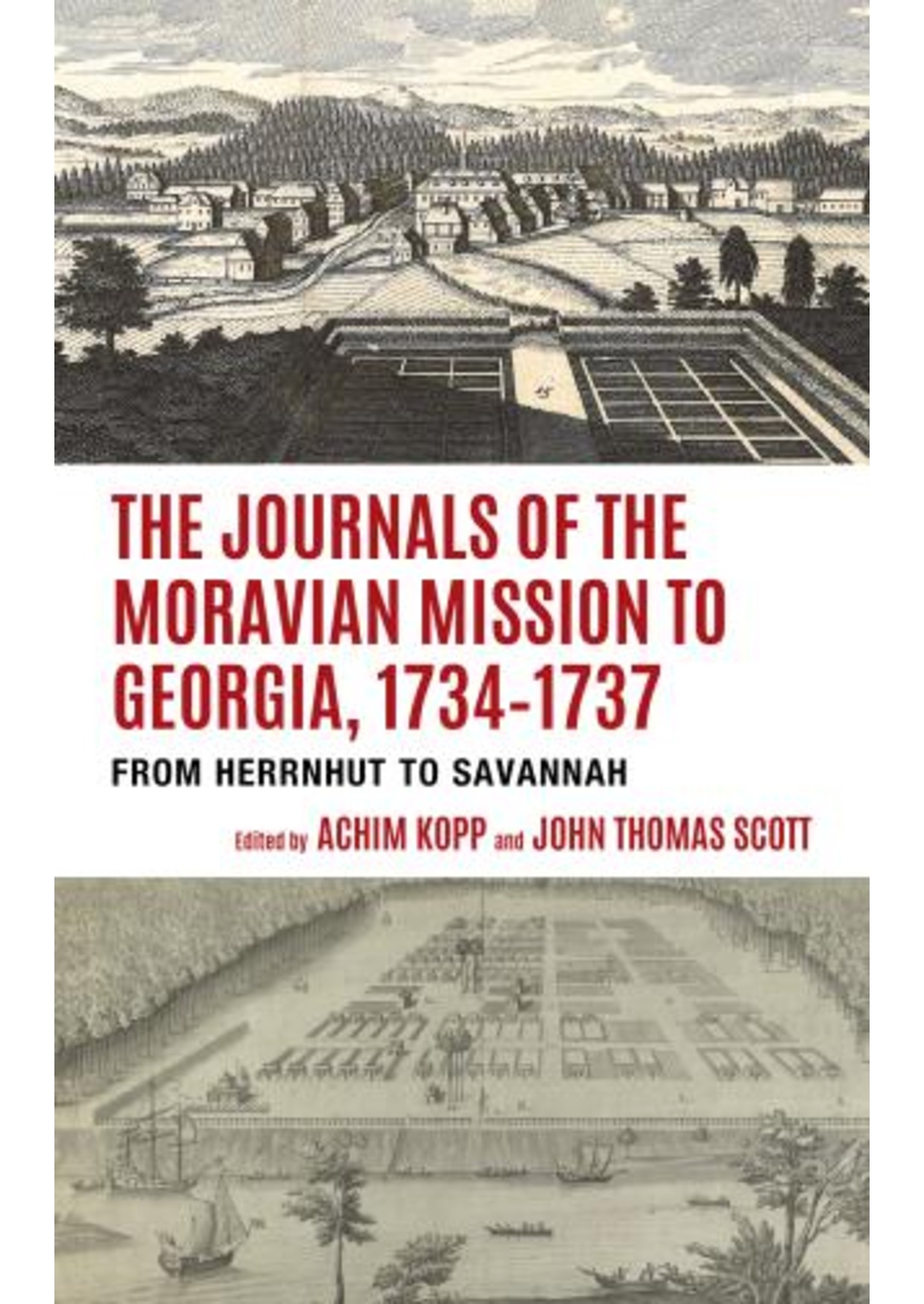

Welcome and thanks for joining us on How My Book Began. I’m Nate Carpenter, managing editor of Lehigh University Press. I'm here today with two scholars, Tom Scott, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Professor of History at Mercer University, and Achim Kopp, who is Professor of Foreign Languages and Literature in the Department of World Languages and Cultures at Mercer. We're here talking today about their book, The Journals of the Moravian Mission to Georgia. 1734 to 1737, which is a collection of translated and transcribed journals of Moravian missionaries who travel from Germany to the British colony of Georgia in the eighteenth century. Thanks so much for joining us, Tom and Achim.

Tom

Thank you for having us.

Achim

Great to be here, Nate.

NRC

This is a book that is really a primary source collection of journal entries from these four missionaries that came from archives in Germany. Talk a little bit about the project. How did this begin? How did you come across these materials?

Tom

I'm an early American historian and have been specializing on early Georgia for 25 years now. The project I began working on was a project on two British mission aries who came to Georgia, John and Charles Wesley. I was working on their experiences in the colony of Georgia and I ran across an article, a scholarly article from the late 1970s [by James Nelson], that made reference to some of these journals that were held at the Unity Archives in Herrnhut, Germany. And the other source was a book that was written more than a century ago by a scholar named Adelaide Fries. She was the archivist at the Moravian Archives in North Carolina and had written a book that made references to journals of Nitschmann and some of the others. I had never seen references to any of these. I began to wonder where are these? What are these? I reached out to James Nelson and asked him did he have transcripts? I also reached out to the North Carolina Archives to see if perhaps Adelaide Fries had left full translations. I found out she hadn’t, but Nelson tipped me off that the Library of Congress had these journals in negative microfilm---where the print is white and the background is black. I contacted the National Archives, and they sent me a couple of xeroxes of these documents as samples. And that's really the point where Achim comes into the story. I do not read German and so I asked him over to my office one day to look at these.

aries who came to Georgia, John and Charles Wesley. I was working on their experiences in the colony of Georgia and I ran across an article, a scholarly article from the late 1970s [by James Nelson], that made reference to some of these journals that were held at the Unity Archives in Herrnhut, Germany. And the other source was a book that was written more than a century ago by a scholar named Adelaide Fries. She was the archivist at the Moravian Archives in North Carolina and had written a book that made references to journals of Nitschmann and some of the others. I had never seen references to any of these. I began to wonder where are these? What are these? I reached out to James Nelson and asked him did he have transcripts? I also reached out to the North Carolina Archives to see if perhaps Adelaide Fries had left full translations. I found out she hadn’t, but Nelson tipped me off that the Library of Congress had these journals in negative microfilm---where the print is white and the background is black. I contacted the National Archives, and they sent me a couple of xeroxes of these documents as samples. And that's really the point where Achim comes into the story. I do not read German and so I asked him over to my office one day to look at these.

Achim

It was in the summer of 2004 that Tom contacted me. In fact, he hired me. He had a little research money in his department and he hired me over the summer to translate some of the Journals. And so I started, and as I was doing that, I found it so fascinating. My background is in English linguistics. My doctoral dissertation was on the English variety spoken by Pennsylvania Germans. And so when I saw these journals it was kind of similar to what I had been working on before, and so I really got into it. And out of this grew then a collaboration over the subsequent summers. I always translated some of the texts and over the years we gathered enough materials that it actually was then enough for a volume that we published in 2023.

NRC

What were the conversations in those early days like with the archives?

Tom

Once we determined that the microfilm was unusable, then it was clear to us that if we were going to proceed, we would have to work directly with the archives. They were very receptive right from the beginning. We had a tremendous experience with them. It was a relationship that lasted more than a decade. We took a trip there in the early 2010s as a kind of scouting trip. How big were these documents? How many pages were they? Are they translatable in the original document form or were they largely unreadable as well? We spent about a week at the archive. I think it was 2011. One of the services that the archive had, that really made the project I think workable, was to have someone on site transcribe the documents into Word documents for us that then Achim could translate. The amount of labor to sit there and transcribe otherwise would have probably made the project unfeasible. The work that the transcriber did was absolutely crucial to the work that we did.

Achim

Especially at our second visit to the archives, we then checked the transcription and we found that it was really, really well done.

NRC

One of the things you note in that introduction is th at you see this as something that's being given to the scholarly community. Scholars of Moravian history, or missionary history, or scholars of eighteenth-century America would now be able to have access to primary source materials that otherwise would not be accessible.

Tom

Right, that that was really important to me. The only references I could see early on were these two that I mentioned previously. And the location of the archives I think is particularly important. Herrnhut is in the southeastern corner of Old East Germany, and so for most of the twentieth century it was not really accessible to Western scholars. I think this helps explain why these sources had not been tapped previously. Achim and I happened upon them at a moment when they were accessible. Part of the difficulty also is that the documents, and Achim can speak more directly to this, the documents are written in a script that is now archaic in Germany. It's not only in a language other than English, it's in a script that is not well known to even to Germans today. And so there's a triple layer of difficulty---a difficult place to get to, they were written in a language other than English, and they are in a script that even German scholars might have some difficulty with. For me, I wanted to bring these forward to my fellow historians, sociologists, linguists, my fellow scholars, to make use of.

Achim

And it was interesting to see the variety of materials that these journals were written on. It was not uniform. I guess paper was scarce at the time and so they used every little scrap paper they had. There are large sheets, but there are also very small little pieces of paper, often written on both sides. It was really interesting to see that difference. And that also made it harder to decipher. They are also deteriorating. There are instances where the margin is torn, where not every word is visible =. Basically, they're in good shape, but the material is after all from around the 1730s. So it is quite old. It's not like a modern book.

NRC

At what point had you decided this needs to be an edited in volume of these journals?

Achim

For a long time, we called this a sourcebook. The idea was to make it a bilingual edition to have both the German journals and a translation, side by side. But over time we gathered more and more material and it became too much for a bilingual edition and so we abandoned that plan and made it strictly into a translation primarily for an English speaking audience.

Tom

After that first trip to Herrnhut we came fairly quickly to a decision. There are a few other journals that we have transcriptions of, and there are also a number of letters from some of the journal authors that are at Herrnhut. We looked at those and we eventually made the decision that we would do just these four journals partly because they were all journals or reports of some sort. We also chose these because they're chronologically grouped together in a fairly tight frame. And, this period from 1734 to 1737 is the high watermark of the trustee Georgia experiment. We thought these could be source materials that would speak to a moment that was important in the history of early Georgia.

NRC

One of the wonderful things from a reader's perspective are the profiles that you provide. What prompted a decision to provide context and background for the people we encounter in these pages?

Tom

As a historian you'll run across the name of a person in the original or in the published version of the original document and you don't know who that person is. You don't quite know how they fit into the larger document that you're working with. So some of it came just from my frustration over the years working with published original documents, wanting to have information about names or sometimes places that I came across. The other thing I’d say is most of my scholarship is concerned in one way or another with biography or biographical sketches. And so I'm drawn immediately to individual people's stories. I'm fascinated by biography.

Achim

For me they helped me to understand, as I was translating these texts, to get the big picture. There was a lot of variety in the way the names were given. So partially the German names were not always spelled the same way, but especially also the English names or the Native American names they appear in a large variety of variants in the texts. That's why we added this chart at the end of book, where we give the different variants of names.

Tom

There was a reference in the original documents to a Sergeant Phillips. There was no Sergeant Phillips in early Georgia and so I puzzled and puzzled about who that was. Finally it dawned on me. There was a Sir John Phillips. But what the German heard was Sergeant and so he wrote that down. So that's an example of how there sometimes had to be a little bit of sleuthing to figure out what it was they were writing, and who it was they were talking about.

Achim

It was very interesting to see how these writers got better and better in English. When they first came into contact with English speakers their knowledge of English was limited. A lot of the spellings of the names were very German. But as they spent more time with the English speakers they got better and better spelling the names much more in an English way.

NRC

How did your relationship as colleagues change overtime as a result of this project?

Tom

This is one of the blessings of this project. You know, the process overlapped COVID. We'd started it before COVID. And one of the strange quirks is that COVID might have accelerated our effort because we were able to continue the project on a weekly basis. We would Zoom and share the document that we were working on. We would go through it paragraph by paragraph, page by page--- “Here are some rough spots.” “How do we fix this?” And then often I would go away with some tasks to do and Achim had some tasks. A lot of the work was done remotely, but in some ways that that might have actually helped us in a strange way.

Achim

Out of this project, one result of it, I think was friendship. I think we really grew to be friends. And of course that helps us now. At some point I became associate dean and then just recently Tom became dean. We are collaborating in the Dean's office now and we have a really wonderful relationship, and that has a lot to do with this project.

NRC

Achim and Tom, thank you so much for joining us today to talk about your work on your research. Wishing you many more joint research trips to Germany!

Tom

That would be a delight.

Achim

Thank you. It was a pleasure talking to you.